President Trump is set on the economy to grow beyond 5 percent real GDP. But high growth has a natural ‘side effect’ and that is a strong dollar. Reducing the trade deficit to spur growth increases domestic investment and appreciates the dollar. Trade tariffs hurt other economies and weaken their currencies. That too raises the value of the dollar. Resolving lower tariffs and trade barriers by invest and build in the U.S. will drive up demand for the dollar. Thus, a policy of targeting a lower trade balance has a paradoxical effect on the dollar and the economy.

One reason is corporate earnings and cash held overseas. The Bureau of Economic Analysis estimates $300 billion in overseas corporate earnings returned to the U.S. in the first half of 2018. This propelled the economy to over 4 percent real GDP and appreciated the dollar by 10 percent in real effective terms. Perversely, tariffs on foreign goods and retaliatory tariffs by other countries led to foreign buyers buying more U.S. goods before the tariffs kicked in. U.S. exports of soybeans for example soared to $4.14 billion in May, twice as much compared to a year earlier. This boosted GDP as many companies appear to have increased inventories and hoarded key materials ahead of tariff-related price increases in July.

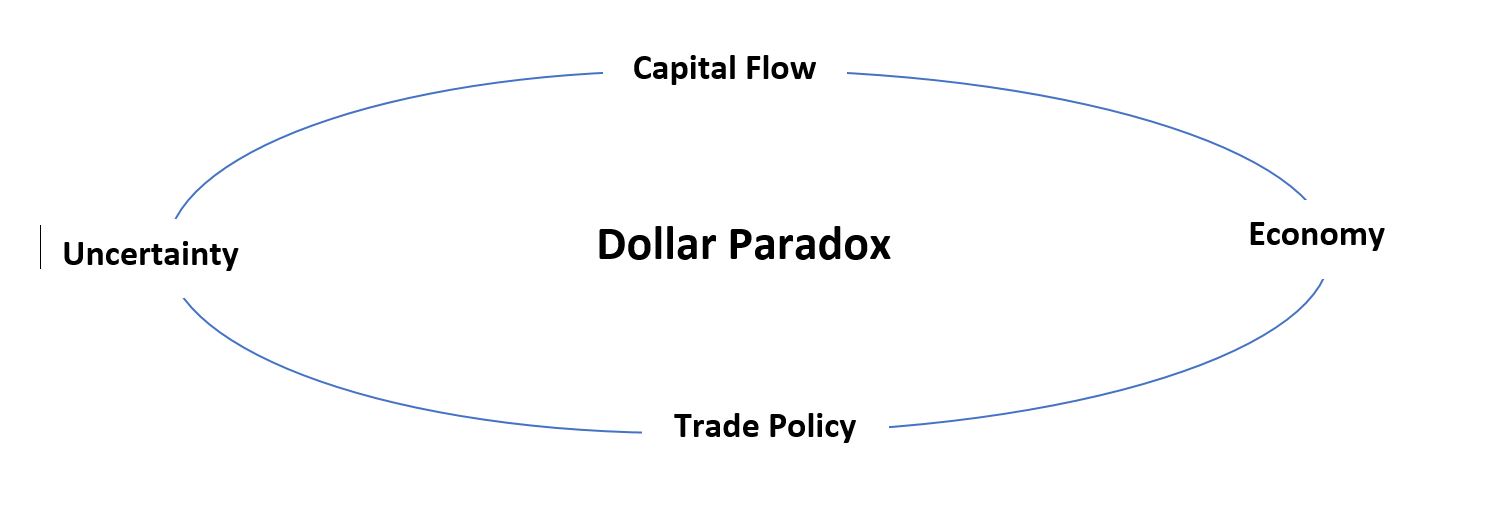

As more trade measures followed, uncertainty in markets increased and led to more capital inflows bolstering the economy. Emboldened by a strong economic performance, the Trump administration enacted more trade policy actions causing further uncertainty and capital flows (see diagram Fig.1). What the U.S. economy suffers from is “dollar paradox” where trade policy uncertainty leads to economic strength to the point of a potential surge of the dollar.

Figure 1 : Dollar Paradox

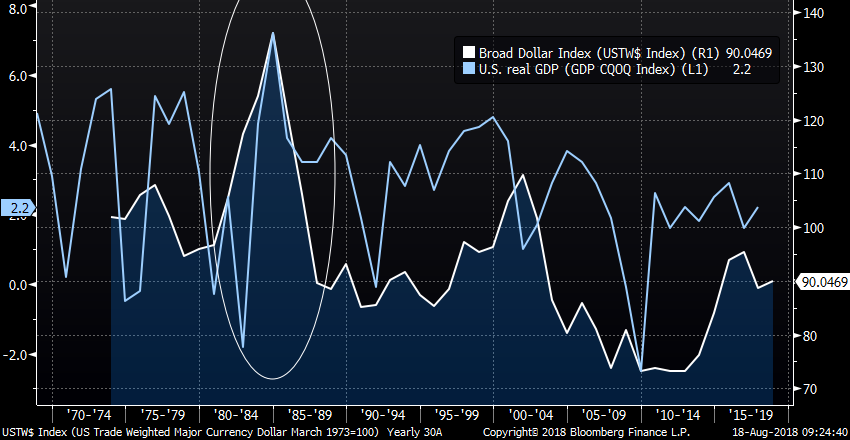

Past appreciation of the dollar have been linked to high GDP growth. Take the broad trade weighted dollar index compared to U.S. real GDP (see Fig. 2). In the mid-1980s when real GDP reached 6 to 8 percent annualized, the dollar surged by over 40 percent. During this time, trade policy in the Reagan administration was formulated as a “strategic retreat”, a military maneuver. The goal was free trade but domestic political pressure moved the administration to apply “voluntary restraint agreements.” Such were Japanese car exports restrictions, a 100% tariff on Japanese electronic products, a 45% duty on Japanese motorcycles for the ben¬efit of Harley Davidson, and a reduction of U.S. steel imports by Korean, Japan and Mexico. The effect on the economy was high growth, narrowing trade balance and a sharply surging dollar.

Figure 2: Dollar and GDP

A rising dollar on high U.S. growth does not come without costs. In today’s environment of trade protectionism, there are some unique aspects. The U.S. is placing tariffs and sanctions in response to political disputes, such as provoked defiance by Turkish officials about an U.S. pastor In turn, the U.S. retaliates with more tariffs. This has caused the Lira to plunge by 30 percent and put Turkey into a self-made financial crisis. This is what markets known as the “defiance loop.” The more Turkey gets defiant, the more tariffs follow and punish the currency and the local economy.

The side effects are contagion to other weaker emerging market currencies like the Rand or currencies like the Ruble or Yuan that are also recipients of U.S. tariffs. In addition, cross border bank exposure to Turkey has been revealed and is a template for such risk to compound if other currencies experience what the Lira went through.

What is the biggest risk is a dollar surge if Trump’s inward policy of narrowing trade balances and high growth succeeds. In the 1980s, Reagan’s appearance of “free trader” came along with geopolitical tension with Russia and resulted in an “arms race.” The administration’s latest defense bill is aimed at that concept of arms race with China and others. This is another force on top of the trade war that could set up the U.S. economy to temporarily grow at 6 to 8 percent.

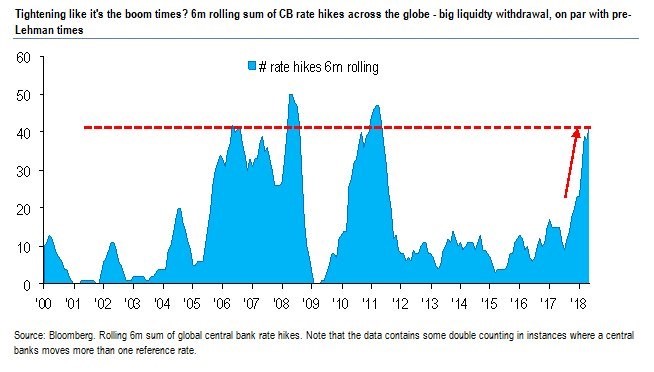

A strong dollar supposed to be a reflection of confidence in the U.S. economy. Paradoxically it comes with costs and benefits. The U.S. may face a hard slowdown once dollar strength reaches a peak. Global central banks are responding to dollar strength by tightening to pre-crisis highs (see Fig. 3). The benefit is that a strong dollar has provide many countries with a 10 to 15 percent depreciation that could bolster their trade competitiveness with countries outside the U.S. The end result is trade surpluses and deficits narrow or even flip. History has shown those periods end with a recession.

Figure 3: Central Banks Rolling Hikes

Comments