One possible effect stemming from the Brexit and U.S. elections outcome could have significant consequences: central banks relinquish their independence. There are academic proposals that call for central banks to maintain “operational independence” but give up political independence. There has been rhetoric during and post campaigns that argue for a change of central bank influence, different board and Chairman appointments and even a call to return to the gold standard. Politically motivated changes of a central bank have been associated with periods of high inflation. However, removal of central bank independence could also play out differently, for example by way of market forces. There are three ways how that may happen:

1.Loss of control over long maturity interest rates

2.Loss of control over the currency

3.Default or restructuring of government bonds held by the central bank

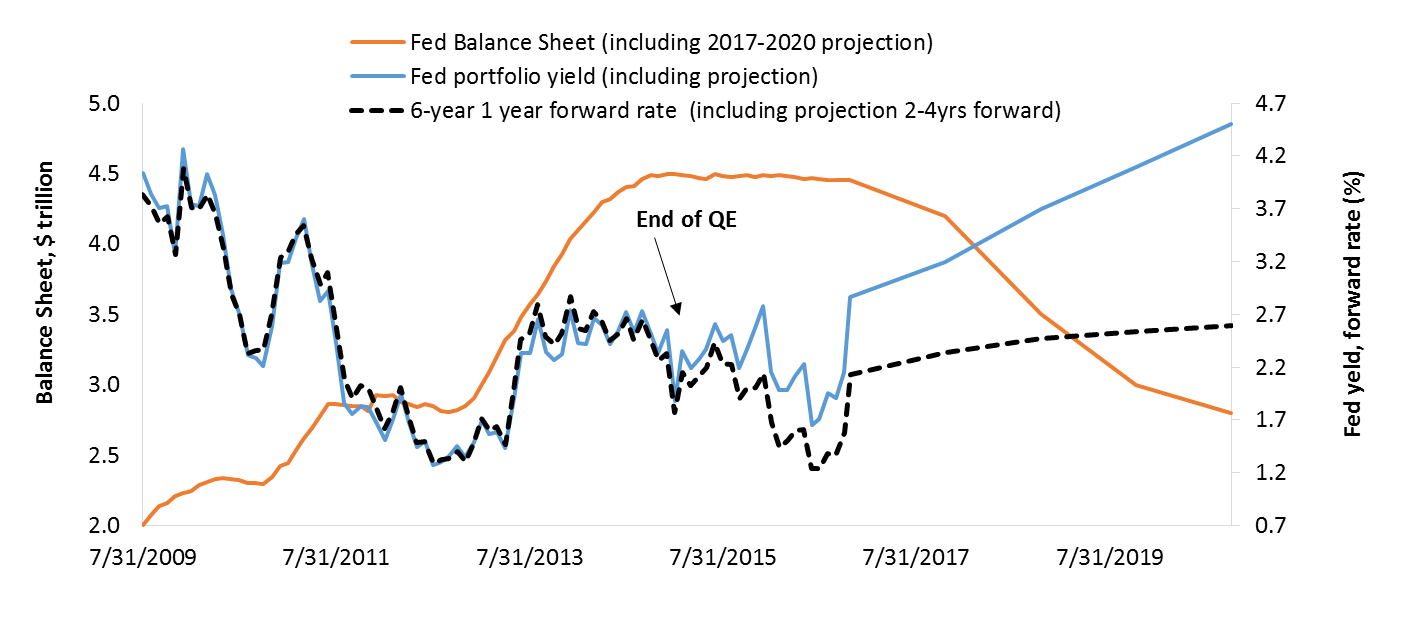

For a brief period, central banks were able to “control” longer maturity rates by forward guidance, QE and implied by Treasury bond holdings on the balance sheet, known as the “portfolio yield.” This is a weighted average yield of the bonds held in the central bank’s portfolio. As an example in Figure 1, the yield of the Fed’s portfolio tracked closely what was expected in the market expressed by forward rates.

If the economy sees a further pick next year, the Fed Funds rate may be hiked to a level where the Fed could decide to end reinvestment of principal and interest of its Treasury and mortgage holdings. When the balance sheet contracts, the portfolio yield could go up significantly. Figure 1 shows a linear extrapolation of the portfolio yield, ending at 4.5 percent when the Fed's balance sheet is below 2.5 trillion.

Market expectations on the other hand remain currently “underpriced” to a scenario of the balance sheet shrinking. At some point, markets would recognize the change of the balance sheet is an adjustment of the Fed’s projected path of future interest rates, and price expectations according to the portfolio yield projection. That could present a situation where central banks may lose "control" over long maturity interest rates. If that were to happen, central banks lose ability to make interest decisions independently from financial markets. That would be an example where the central bank lost independence as a result of market forces.

Figure 1: Balance Sheet and Rates

Source: Bloomberg, Federal Reserve, monthly data, 2009-2016 including 2017-2020 projections of rates and balance sheet

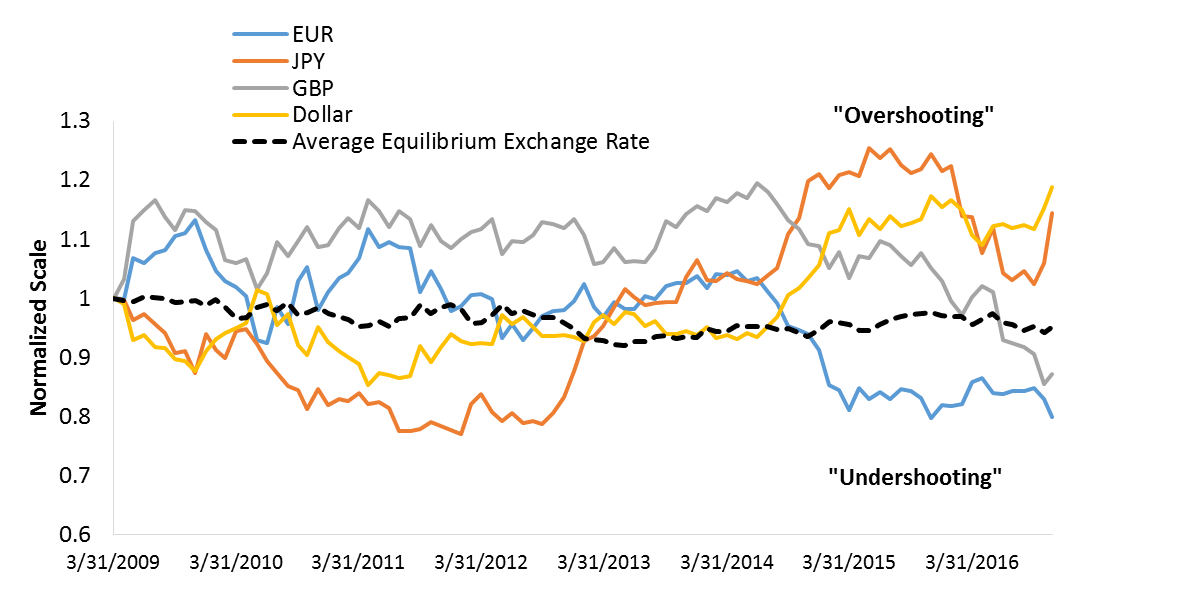

In recent years, currencies have responded with greater sensitivity to signals of intended tightening or (quantitative) easing. As such, currencies have experienced “overshoots or undershoots.” Figure 2 shows the Yen, Sterling, Dollar and Euro compared to their (simple) average equilibrium exchange rate (see for description below the chart). What can be seen is that major exchange rates are overshooting (Dollar, Yen) or undershooting (Sterling, Euro).

Exchange rates deviating too far from equilibrium is a sign central banks cannot control the long run value of the currency.

Without a currency anchor, risk of inflation (too weak currency) or deflation (too strong currency) increases to a level the central bank policy decisions can become ineffective, and may erode operational independence to set interest rates. In both cases, significant interest rate or currency volatility may lead to central banks unable to control the situation without the interference of the political spectrum.

Figure 2: Currency Overshoot and Undershoot

Source: Bloomberg, Bank of International Settlements. Equilibrium exchange rate is measured as expected real exchange rate = real effective exchange rate. Expected real exchange rate = spot + 1-year forward points adjusted for annual inflation. Euro, Yen, Pound and Dollar are normalized 3/1/09 = 1 (start of QE1 in the U.S.) and expressed in real effective terms.

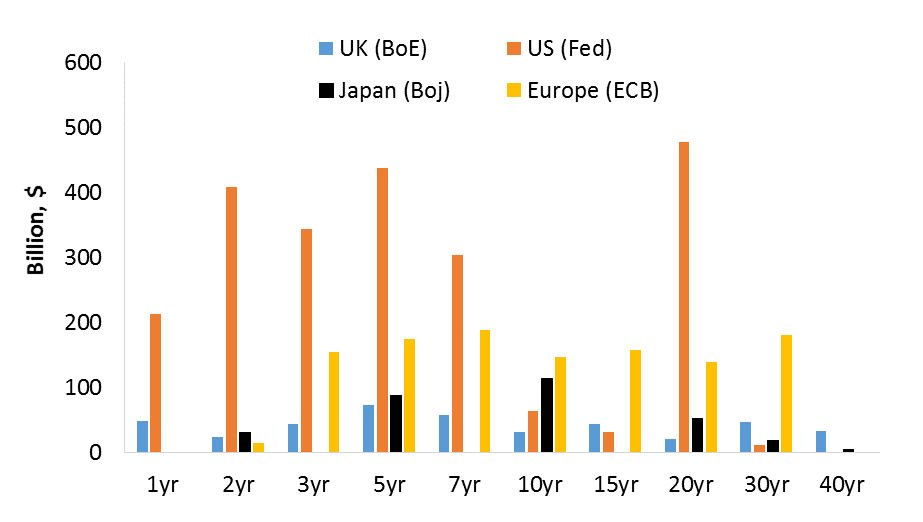

Another kind of independence loss is when a central bank may have to participate in a future debt restructuring or is face with a default. When any of the major developed economies would face a default of government debt, the expectation is the central banks’ printing press will eliminate the risk. Considering today’s sizeable holdings by central banks (Figure 3), the printing press may not remedy. Because most major developed government bond markets (except Europe) do not have specific rules for an orderly restructuring, central banks would be dependent on market forces to determine what the appropriate haircut (i.e. discount) on debt would be.

Figure 3: Central Bank Holdings of Government Bonds

Source: New York Federal Reserve, Bank of England, Bank of Japan and European Central Bank. Amounts converted to dollars, in billions by maturity.

Investment Implications

The loss of central bank independence described by the three practical ways, could have very damaging long term consequences. For one, pensions, life insurance and the financial system could be paralyzed by mounting losses on government bonds. Capital flows would be substantial and cause high financial market volatility. The end result may lead to extremes such as debt default or debt crisis or rampant inflation or deflation. At today’s valuation of bonds, stocks, commodities and currencies, expectations of a central bank crisis through loss of independence remain benign. The Brexit and U.S. Presidential elections were important political pivots where the discussion of a change of central bank independence has heated up. Investors should closely monitor currency markets for significant movements as a first sign of a move away from central bank independence. The potential loss of central bank independence could be the "Great Unwind" of past two decades of low, stable inflation and steady growth of financial assets.

Comments